Africa’s Role in the Slave Trade: Empires, Resistance, and Forgotten Realities

The transatlantic slave trade is often portrayed as a European-driven atrocity, but its machinery relied heavily on African participation. Long before the first Portuguese ships arrived on the West African coast, slavery was already embedded in African societies, particularly through the trans-Saharan slave trade, which for centuries sent enslaved Africans eastward to North Africa and the Islamic world. However, the arrival of Europeans in the 15th century—first the Portuguese, then the Dutch, British, French, and Danes—ushered in a new era of mass human trafficking. Coastal forts like Elmina, Cape Coast, and Fort Visão in Accra became hubs of this trade, but they could not function without the cooperation of powerful African states..

African Empires That Fueled the Trade

Several African kingdoms and empires actively participated in the transatlantic slave trade, capturing and selling prisoners of war or rivals to European merchants:

Asante Empire (Ghana): Founded in the 17th century, the Asante became one of the most powerful states in West Africa. They traded enslaved people for firearms and luxury goods, and used slave labor extensively in agriculture and mining. Even after Britain abolished the slave trade in 1807, the Asante continued to use and trade slaves well into the 1920s, with British colonial authorities largely ignoring the practice.

Dahomey Kingdom (Benin): Known for its militarism and centralized control, Dahomey was deeply entrenched in the slave trade. The kingdom resisted abolition efforts and continued trading slaves until the late 19th century. Some sources suggest that slave trading persisted in Dahomey until around 1887, when the French finally overpowered the kingdom and imposed colonial rule.

Oyo Empire (Nigeria): A dominant Yoruba state, Oyo supplied thousands of captives to European traders. Its economy was heavily reliant on slave raids and trade routes leading to coastal ports.

Kingdom of Whydah (Benin): Before being absorbed by Dahomey, Whydah was a major slave trading port, facilitating the export of captives to the Americas.

These empires did not merely tolerate slavery—they built political and economic systems around it. The trade enriched elites, funded armies, and shaped diplomacy.

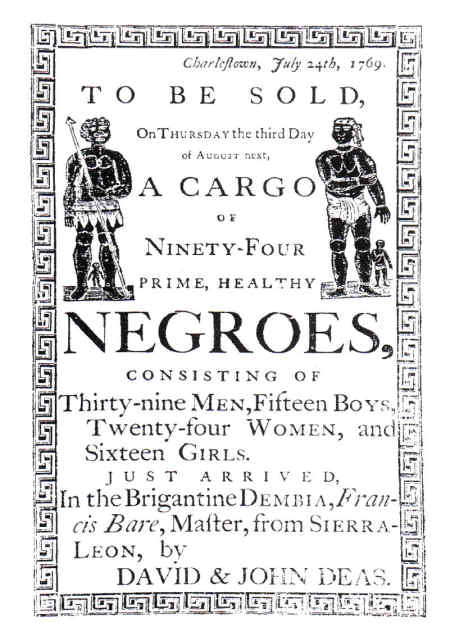

To be sold! A Cargo of Ninety-Four prime, Healthy NEGROS, consisting of 39 Men, 15 Boys, 16 Girls. Just ARRIVED, in the Brigantine Dembia, Francis Bare, Mafter, from Sierra-Leone, by David & John Deas, 1769

🇬🇭 Ghana3d.com Gateway Experience 360

Find your roots and rise — Ghana3d.com Gateway Experience 360 is your ultimate guide to cultural, historic, and soul-stirring adventures. Whether you're returning to your ancestral land or exploring Ghana for the first time, we offer curated journeys that connect you deeply to the spirit of West Africa. From powerful walks through Cape Coast & Elmina slave castles to the vibrant rhythms of Accra’s nightlife. From sacred village ceremonies to awe-inspiring natural beauty — your journey starts here.

- ✔ Instant Confirmation

- ✔ Free Cancellation

-

✔ Best Price Guarantee

You'll receive a full refund if you cancel at least 24 hours in advance of most experiences.

Resistance to Abolition

When European powers began to abolish the slave trade in the 19th century, resistance came not only from merchants but also from African rulers:

The Asante viewed abolition as a threat to their sovereignty and economy. They clashed repeatedly with the British, culminating in wars that were partly fueled by disputes over trade and control.

The Dahomey monarchy openly defied French pressure to end the trade. King Behanzin, the last independent ruler, refused to abandon slavery until French forces invaded and annexed the kingdom in 1894.

Despite formal abolition, slave labor persisted in both regions under colonial rule. British and French administrators often ignored or tolerated slavery, especially when it served economic interests or avoided political unrest.

Fort Visão and the Hidden Tunnel

In Jamestown, Accra, the Portuguese-built Fort Visão (c.1660) stands as a forgotten relic of this history. Beneath its ruins lies a hidden slave tunnel, used to transport captives discreetly from holding areas to the coast. The fort, long ignored by heritage institutions, is now privately owned and inhabited—its legacy buried beneath layers of neglect and silence.

A Shared Responsibility

The slave trade was not a one-sided affair. It was a collaboration between European powers and African elites, driven by profit and sustained by violence. Recognizing Africa’s internal dynamics—its empires, resistance, and complicity—is essential to understanding the full scope of this history.

Only by confronting these truths can we begin to honor the memory of those lost and build a more honest narrative of Africa’s past.